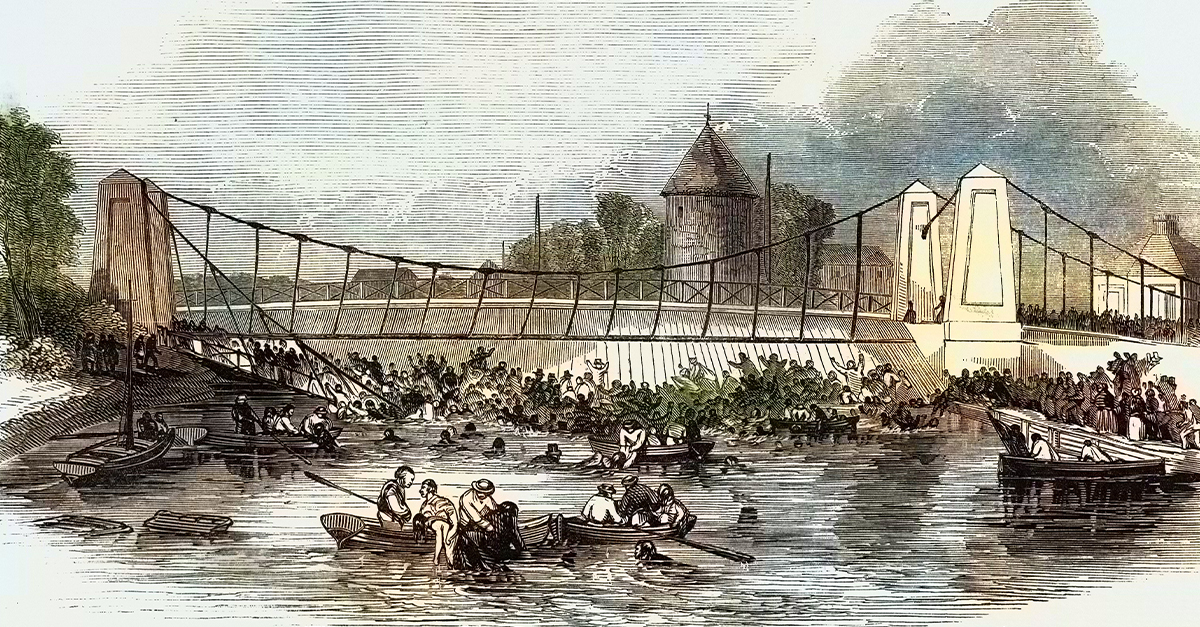

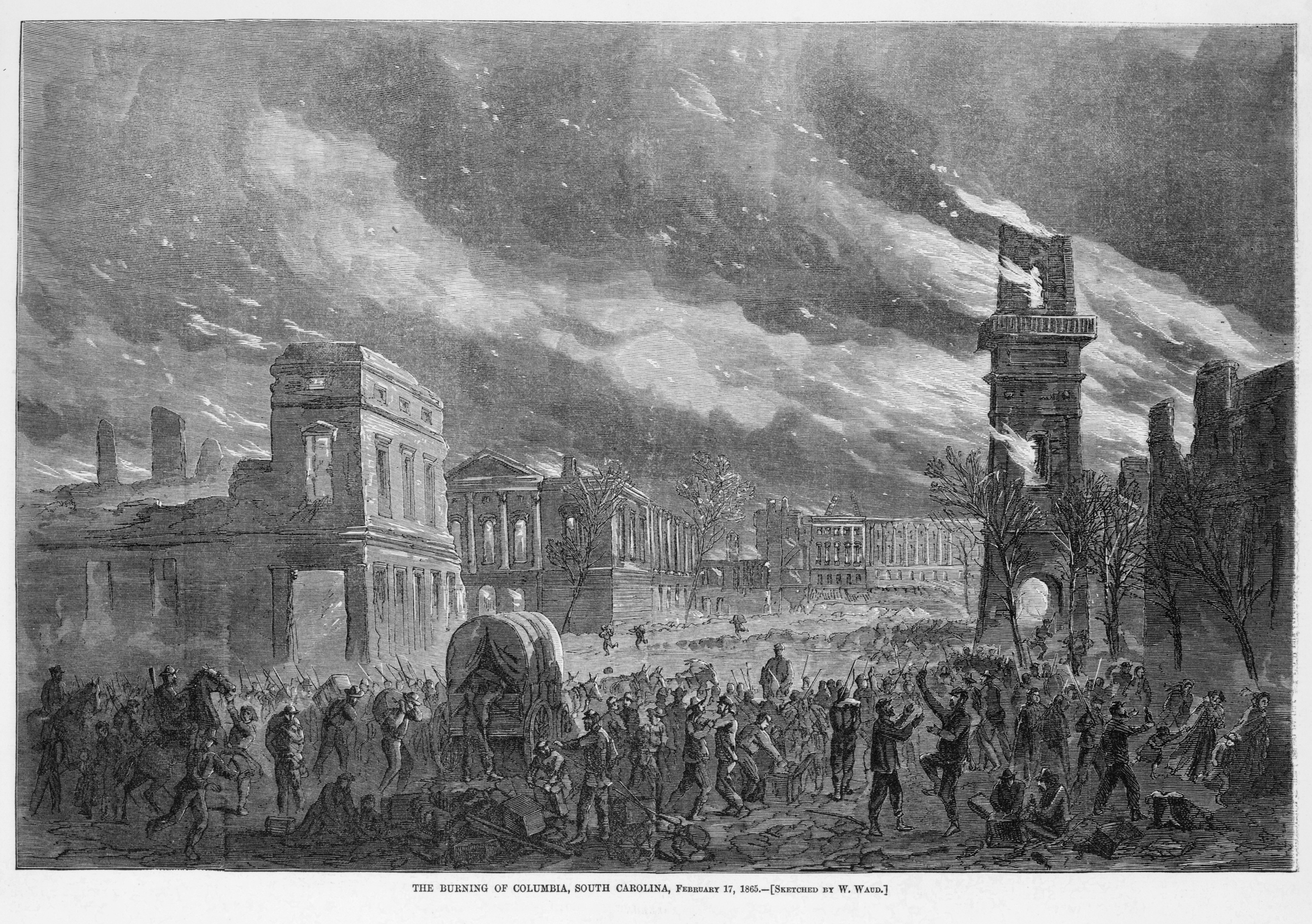

On the night of February 17, 1865, as Union General Sherman’s forces entered Columbia, South Carolina, the city was consumed by fire. By daylight, much of the city lay in smoldering ruins. The destruction was unleashed during the Union occupation, but the true cause of the blaze has been a subject of debate ever since.

A City On The Precipice

By early 1865, the Confederacy was coming unglued. General Sherman had sliced through Georgia during his devastating “March to the Sea” and now turned his sights on South Carolina, the state that had led the charge of secession. As state capital, Columbia had symbolic and strategic value. When Confederate troops evacuated the city, they left cotton bales behind in the streets. Some of these were reportedly set on fire to keep them from falling into Union hands.

William Waud (d. 1878) for Harper's Weekly., Wikimedia Commons

William Waud (d. 1878) for Harper's Weekly., Wikimedia Commons

Sherman Arrives

Sherman’s troops entered Columbia on the afternoon of February 17. By evening, fires were raging all over town. Eyewitnesses, Union and Confederate, told of strong winds that night, that spread the flames quickly. Union soldiers and officers tried to put out the fires in some areas; in others soldiers preferred to take advantage of the chaos by looting homes and businesses.

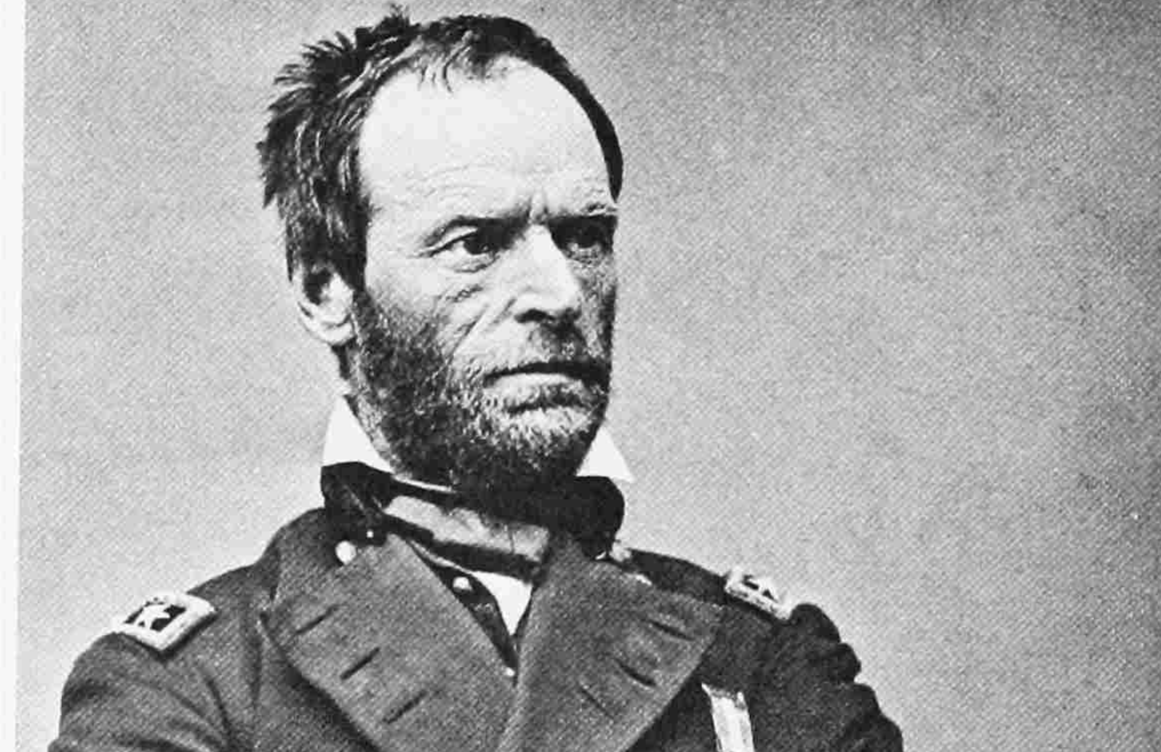

Sherman Stuck To His Story

General Sherman denied any deliberate act to destroy the city. In his memoirs, he put the blame on the retreating Confederates for setting the cotton ablaze, writing: “The whole city was on fire… the high wind had caused it to spread rapidly.” Sherman also pointed out the lack of fire engines, the drunkenness among Union troops and local residents, and the general chaotic situation as the major factors.

Paul J. Scheips, Wikimedia Commons

Paul J. Scheips, Wikimedia Commons

Confederates Point The Finger

Southern observers and leaders gave a very different account. They claimed Sherman’s men deliberately set fires to punish the South for secession. Columbia’s mayor and civilians accused Union troops of drunken rampages, burning down buildings and spreading destruction. The Southern press and postwar Southern writers frequently mentioned the burning as an act of Northern vengeance and fury.

Historians Weigh In

Today most historians say the truth is probably somewhere in between. The combination of burning cotton, strong winds, lax discipline, and general wartime chaos most likely turned a few small fires into a city-wide conflagration. Historian Marion B Lucas, in his Sherman and the Burning of Columbia (2021), notes that while there may have been isolated acts of arson by Union soldiers, there’s no evidence of an organized plan to burn down the city.

Soldiers Broke Into A Warehouse Of Confederate Booze

Some Union soldiers reportedly found stores of whiskey left by the retreating Confederates. On a night of celebration, lacking command oversight, and with easy access to matches and torches, alcohol was a decisive factor. Once a few buildings caught, the embers borne aloft on the wind spread the blaze to the tinder-dry wooden buildings of Columbia’s business district.

Accidental Or Intentional?

The general consensus today is that the burning was a tragic byproduct of war instead of a deliberate act. Union forces certainly weren’t entirely innocent, but there’s no definitive proof of any official order to burn Columbia. Most scholars now view the destruction as the result of a whole slew of factors: Confederate sabotage, conditions ripe for a fire, breakdown of order, and the psychological toll of war on men on both sides.

George N. Barnard, Wikimedia Commons

George N. Barnard, Wikimedia Commons

A Fire That Still Smolders

The burning of Columbia is to this day one of the most controversial incidents of the Civil War’s closing days. For many in the South, it showed the cost of defeat and the utter brutality of total war. Many others saw it as the inevitable result of the destruction of a slaveholding society. The true cause may never be known for sure, but the fire that consumed Columbia cast a long shadow on history.

You May Also Like:

The Greatest Military Geniuses In History

The Origin Of Each State's Name

The History Of The Geneva Conventions And The Red Cross