The Bottom Of The World

Today, a large research station stands right at the South Pole. It’s called the Amundsen-Scott South Pole station, after the two men who led the first expeditions to our planet’s southernmost point in 1912.

But only one of those men made it back alive.

Herbert Ponting/Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge/Getty Images

Herbert Ponting/Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge/Getty Images

Falcon

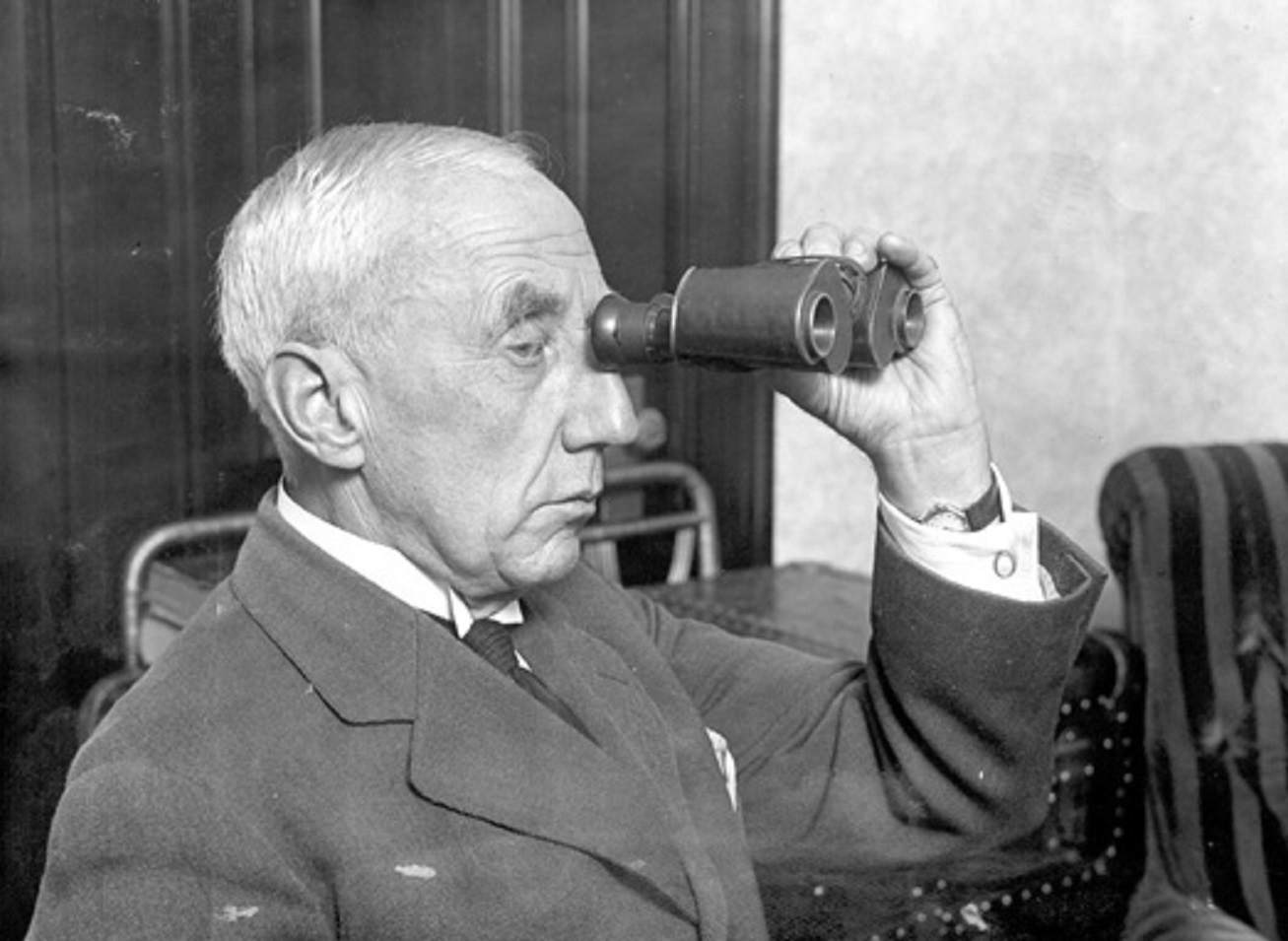

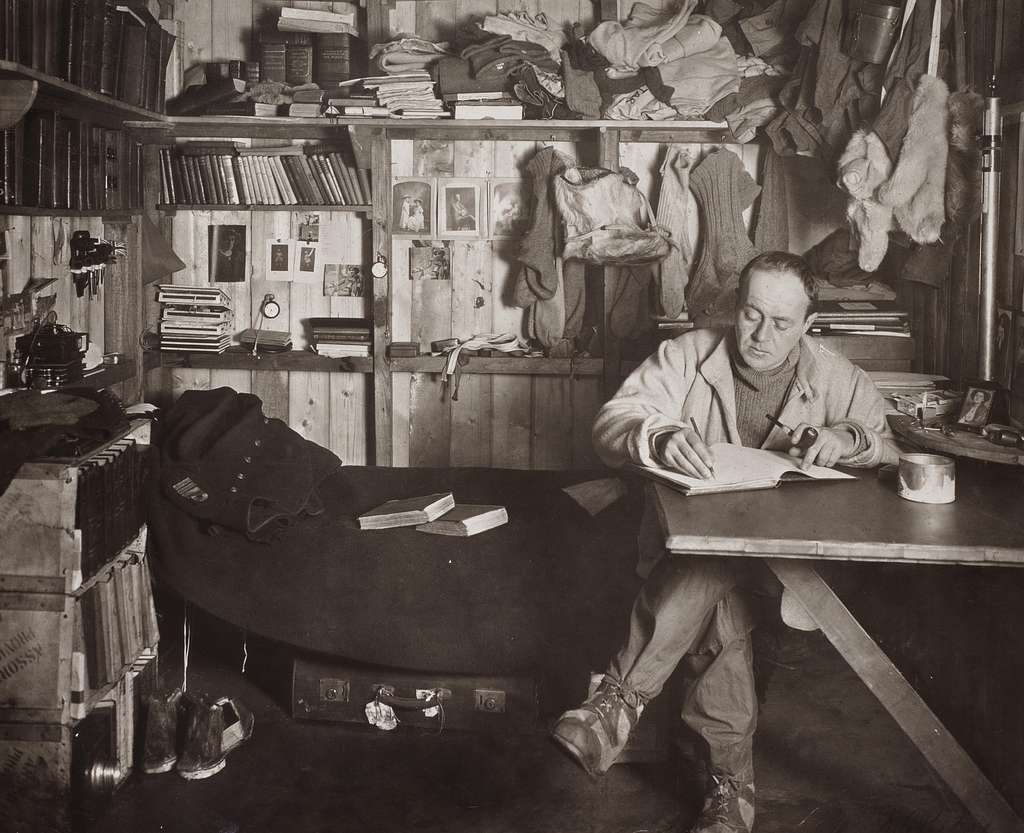

Robert Falcon Scott was a British national hero in the early 20th century. After his Discovery expedition explored further south than anyone had ever been before, he returned to civilization as a living legend.

Herbert Ponting, Wikimedia Commons

Herbert Ponting, Wikimedia Commons

Celebrity Explorer

Scott got to spend his post-Discovery years as a celebrity, traveling the world giving lectures on his travels and writing a detailed record of his expedition: The Voyage of the Discovery. But Scott wasn’t one to retire to a cushy life of speaking tours and memoirs.

Where No One Has Gone Before

That entire time, he knew that the Antarctic’s greatest prize lay waiting in the frozen waste: the South Pole. No human being had yet seen it.

The Race Was On

The world of the 20th century was smaller than it had ever been. There weren’t many “firsts” left for explorers like Scott. But the South Pole was still out there, and Scott wasn’t the only person who wanted to claim it.

Groups from many countries were planning expeditions to reach the South Pole. So Scott threw his hat in the ring.

Scotts ekspedisjonsskip, Picryl

Scotts ekspedisjonsskip, Picryl

Scott Was The Favorite

Scott was the obvious front-runner to make it to the Pole first. His biggest rival, the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, couldn’t be further away—Amundsen publicly announced that he was going to attempt to be the first person to reach the North Pole.

But Scott was in for a rude awakening.

bilinmiyor, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

bilinmiyor, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Terra Nova

Scott started on his way to the South Pole thinking he had no real competitors. But then, when Scott's Terra Nova expedition reached Australia on his way south, he found an unwelcome message waiting for him.

He Was Already Behind

It was from Roald Amundsen, and it simply said: “Beg leave to inform you Fram [Amundsen’s ship] proceeding Antarctica".

Amundsen had tricked them all. Suddenly, the race was on; and Scott was way behind.

SDASM Archives, Wikimedia Commons

SDASM Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Turn Compass To "South"

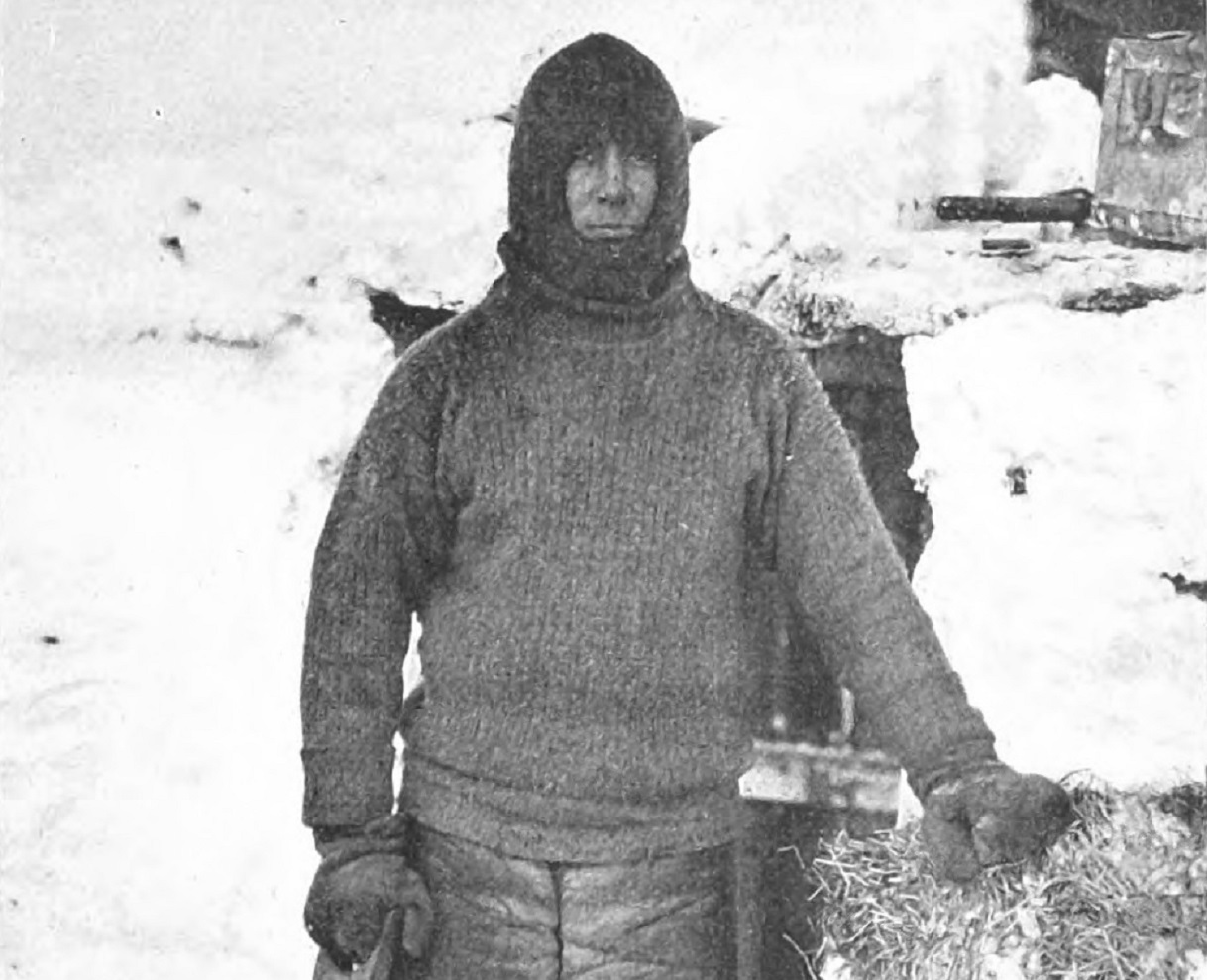

Scott left his base camp on November 1, 1911, headed south. To give him the best chance of reaching the Pole, he started with 16 men, all of them lugging gear.

As they pressed on, they would set up depots with supplies for the return journey, and some of the men would then head back to base camp.

The Final Five

By January 3, 1912, after two months of trudging through the snow, Scott selected the four men who would accompany him to the South Pole. Everyone else were sent back the way they’d come, and those final five set out to win the race to the South Pole.

This was the last time that anyone would ever see them alive.

Bowers, H. R. (Henry Robertson), Wikimedia Commons

Bowers, H. R. (Henry Robertson), Wikimedia Commons

A Sight For Sore Eyes

Scott and his men continued their painful march across the Antarctic, but on January 16, they encountered a sight that left them hollow: a black flag poking up out of the tundra in the distance.

Le Tour du monde, Wikimedia Commons

Le Tour du monde, Wikimedia Commons

The Worst Part

From the moment they saw that flag, they knew what it meant: Amundsen had been here already. They’d lost. And even worse, the hardest part was still ahead of them.

Frederick Cook, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Frederick Cook, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Second Comes Right After First

They reached the South Pole the next day. In his diary, Scott wrote: “Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority. Well, it is something to have got here".

Bonhams Fine Art Auctioneers & Valuers, Picryl

Bonhams Fine Art Auctioneers & Valuers, Picryl

Might As Well

Scott planted a British flag near the Norwegian one that Amundsen had left there 30 days earlier, then he and his men simply turned around and started heading back, defeated.

National Library of New Zealand, Picryl

National Library of New Zealand, Picryl

Clear Skies

The trip to the pole had been horrific, but the way home started off well. Scott’s journal recorded weeks of good progress, but he did note that his party was starting to show signs of wear.

Flickr: Steam Yacht 'Terra Nova', Picryl

Flickr: Steam Yacht 'Terra Nova', Picryl

They Were Getting Run Down

Scott’s companion Edgar Evans was in particularly bad shape. Frostbite was taking his extremities, and Scott admitted that Evans was becoming “a good deal run down".

Herbert George, Wikimedia Commons

Herbert George, Wikimedia Commons

Life In A Desolate Place

Scott decided to give his team a half-day’s rest—at which time Edward Wilson, his chief scientist, discovered rocks containing fascinating fossils, shocking in such a frozen, lifeless wasteland.

Unfortunately, finding fossils was the LAST thing they needed.

Lawrence Oates ,Wikimedia Commons

Lawrence Oates ,Wikimedia Commons

What's The Worst That Could Happen?

Since this was, after all, a scientific expedition, the team added 30 pounds of rocks to their already heavily-laden sledges, despite their already precarious situation.

A Changed Man

Unfortunately, the half-day break they took to collect rocks wasn’t enough for a man in Edward Evans’ state. His mental state began to transform, and Scott noted that he was “absolutely changed from his normal self-reliant self".  Herbert Ponting, Wikimedia Commons

Herbert Ponting, Wikimedia Commons

One Soul Down

Finally, on February 17, Evans collapsed, never to rise again. This was just the beginning.

Herbert Ponting, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Herbert Ponting, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

They Lost Their Anchor

Scott and the other remaining men mourned for Evans, but his demise did come with a grim advantage: they could make much better time without Evans slowing them down.

Unfortunately though, that wouldn’t be enough to save them.

Biodiversity Heritage Library, Picryl

Biodiversity Heritage Library, Picryl

It Wasn't Enough

Everything started to go wrong. The temperature unexpectedly plummeted to below -40 degrees. They arrived at depots to find less fuel than they’d expected. The dog teams that were supposed to meet up with them never arrived.

Scanned from the book Les Grands Explorateurs, Picryl

Scanned from the book Les Grands Explorateurs, Picryl

Resigned To His Fate

In his journal, Scott tried to remain as optimistic as possible, but he knew his chances were slim: "We very nearly came through, and it's a pity to have missed it, but lately I have felt that we have overshot our mark. No-one is to blame and I hope no attempt will be made to suggest that we had lacked support".

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

A Stroll Outside

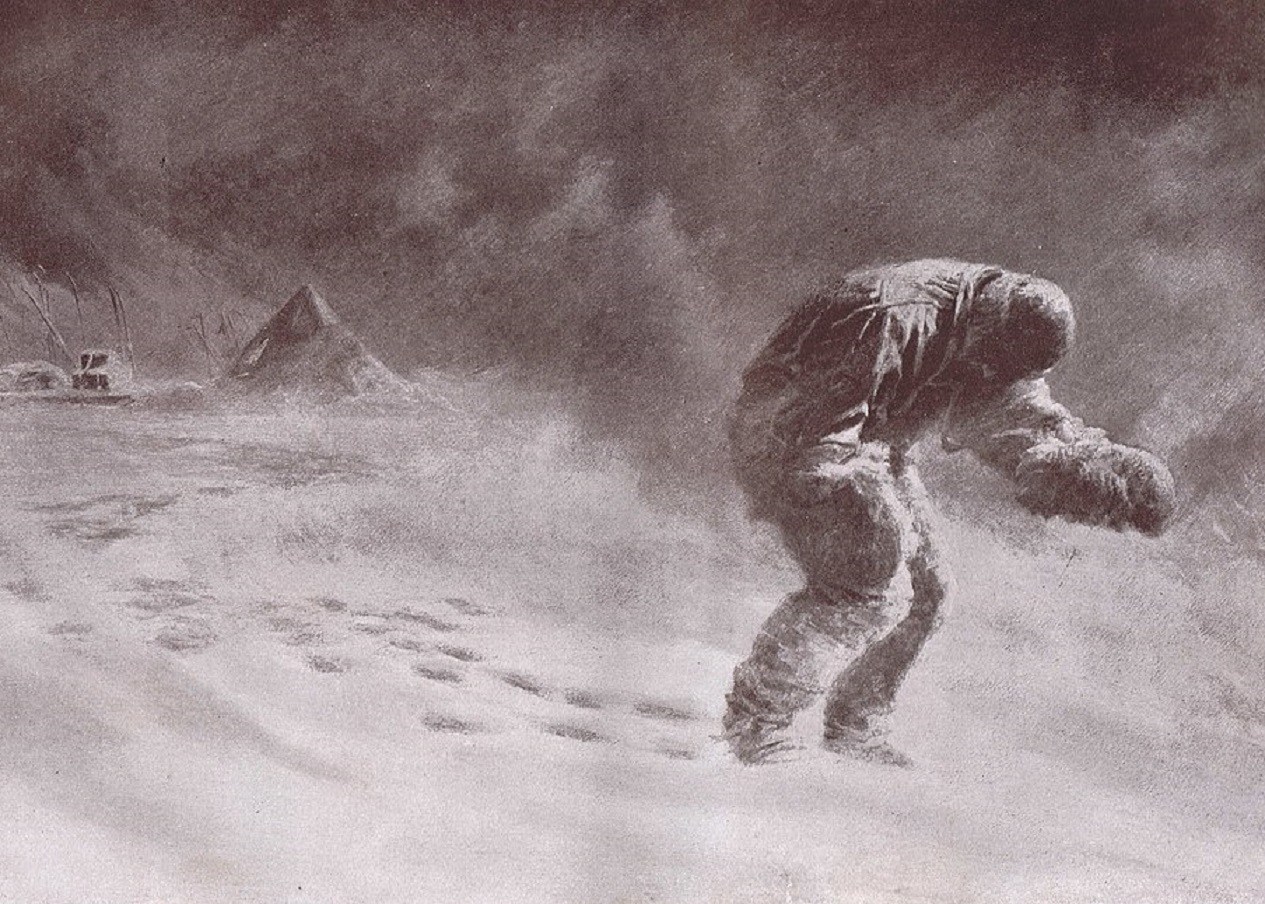

Scott wrote that entry on March 10, 1912—Lawrence Oates’s birthday. And it was on that same day that Oates himself suddenly stood up in their tent and announced: “I am just going outside and may be some time".

Herbert Ponting, Wikimedia Commons

Herbert Ponting, Wikimedia Commons

He Realized What He Had To Do

By that point, Lawrence Oates’s hands and feet were both left completely useless from frostbite. Like Evans, he had become an anchor tied to his companions. So he made a horrible, impossible decision.

Le Tour du monde, Wikimedia Commons

Le Tour du monde, Wikimedia Commons

He Sacrificed Himself

Oates knew he was done for, but hoped Scott and the others might still make it. He courageously walked out into the snow to his doom, giving them the best chance possible. But it was too late.

Even his heartbreaking sacrifice couldn’t save this expedition.

John Charles Dollman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

John Charles Dollman, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Three Remain

By now, there was only Scott and two other men left: Edward Wilson, and Henry Bowers. While the three of them tried to struggle northward, frostbite began to take their toes and the bone-chilling weather refused to relent.

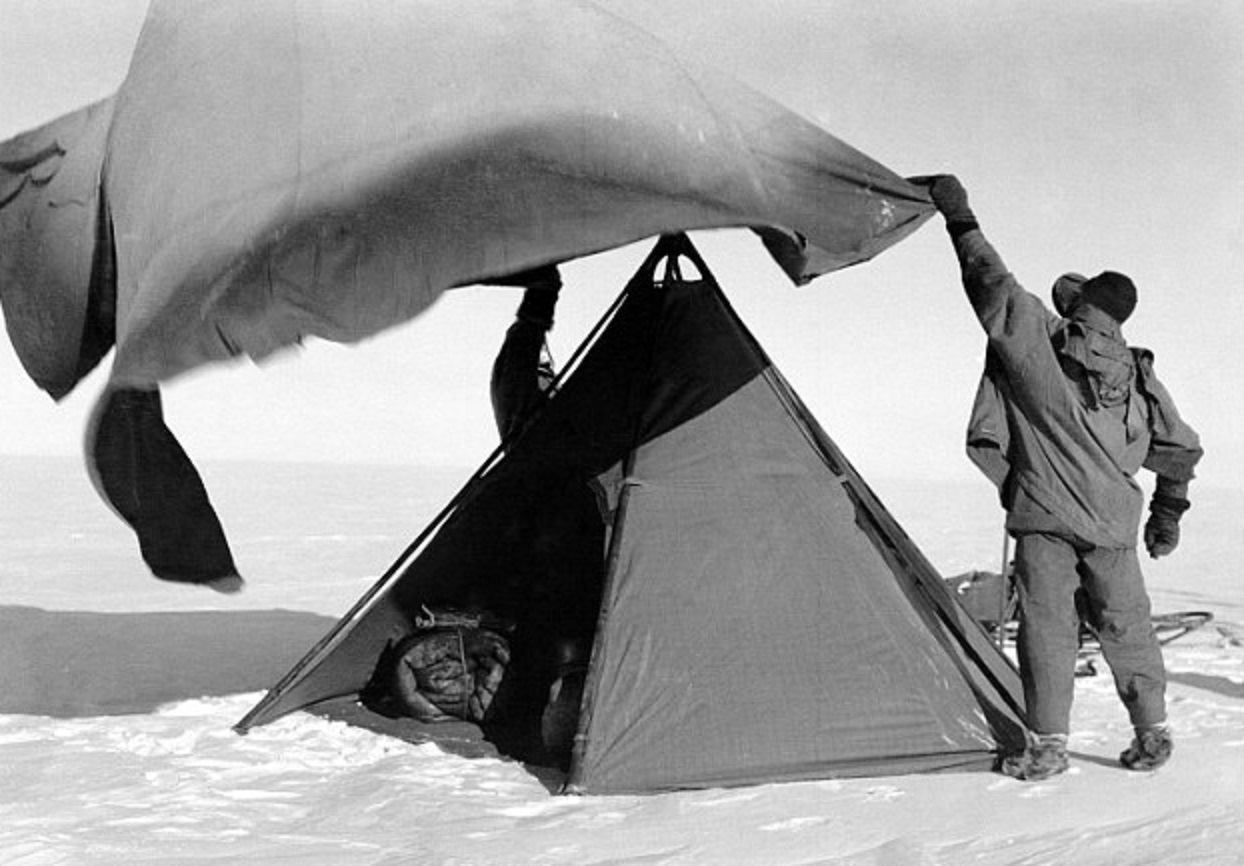

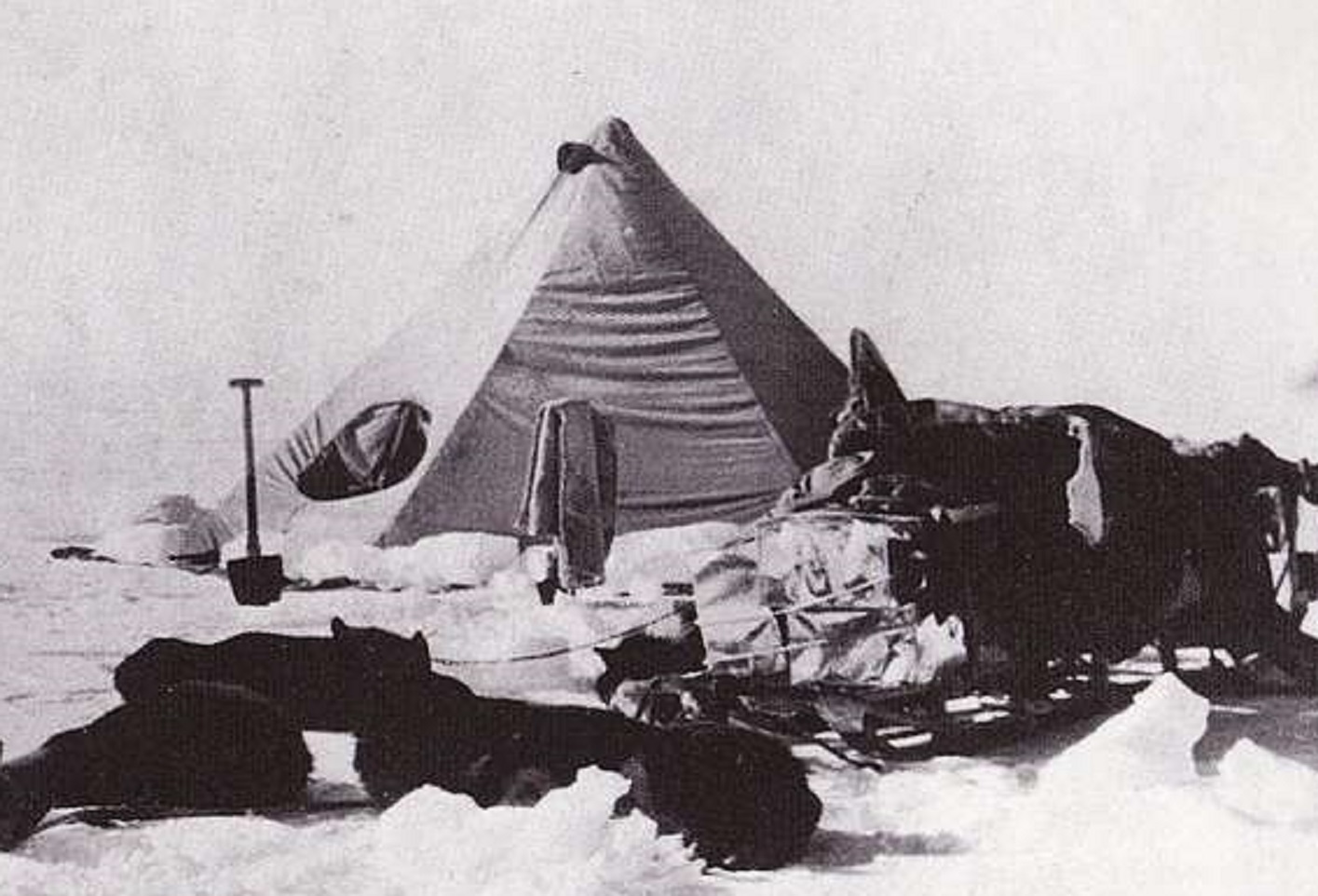

The Coup De Gras

Right when it seemed their situation couldn’t possibly get any worse, on March 20, yet another blizzard hit, and the men made camp one last time.

"For God's Sake Look After Our People"

Nine days later, Robert Scott wrote his final journal entry: “Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity but I do not think I can write more. R. Scott. Last entry. For God's sake look after our people".

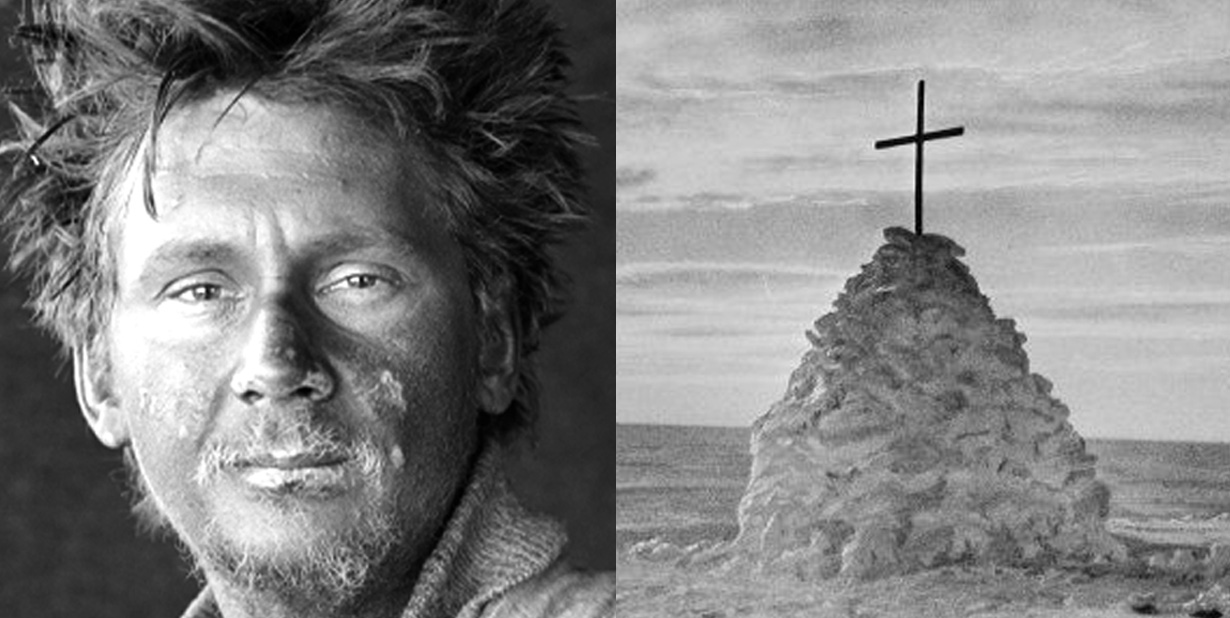

They Remain Where They Lay

Members of the Terra Nova expedition discovered the bodies of Robert Scott, Edward Wilson, and Henry Bowers months later, on November 12, 1912.

Bringing back their frozen remains would be too dangerous, so the crew left them as they lay. They built a cairn of snow over the tent and fashioned a cross out of skis to place on top. They searched for Oates’ body as well, but never found it.

British Antarctic Expedition, Picryl

British Antarctic Expedition, Picryl

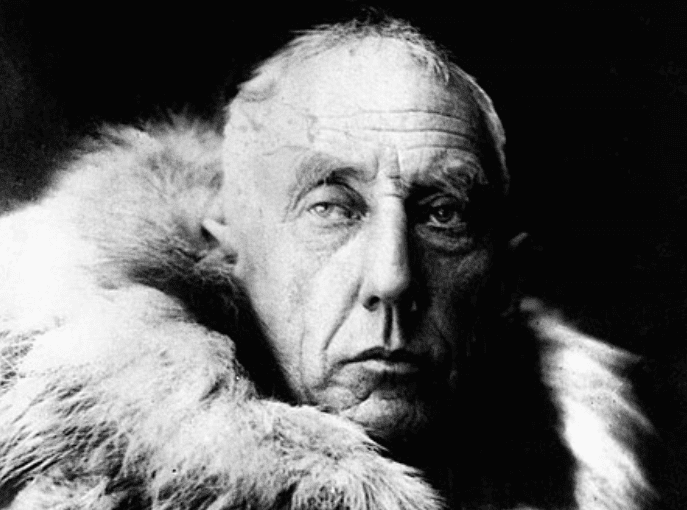

What Went Wrong?

Why did Scott’s expedition fail so tragically? Not only did Roald Amundsen beat him to the South Pole, but Amundsen made it back safely, while all of Scott’s men perished.

History has had lots of different takes on the story.

Scott Polar Research Institute Cambridge Exhibition, Picryl

Scott Polar Research Institute Cambridge Exhibition, Picryl

Who Is To Blame?

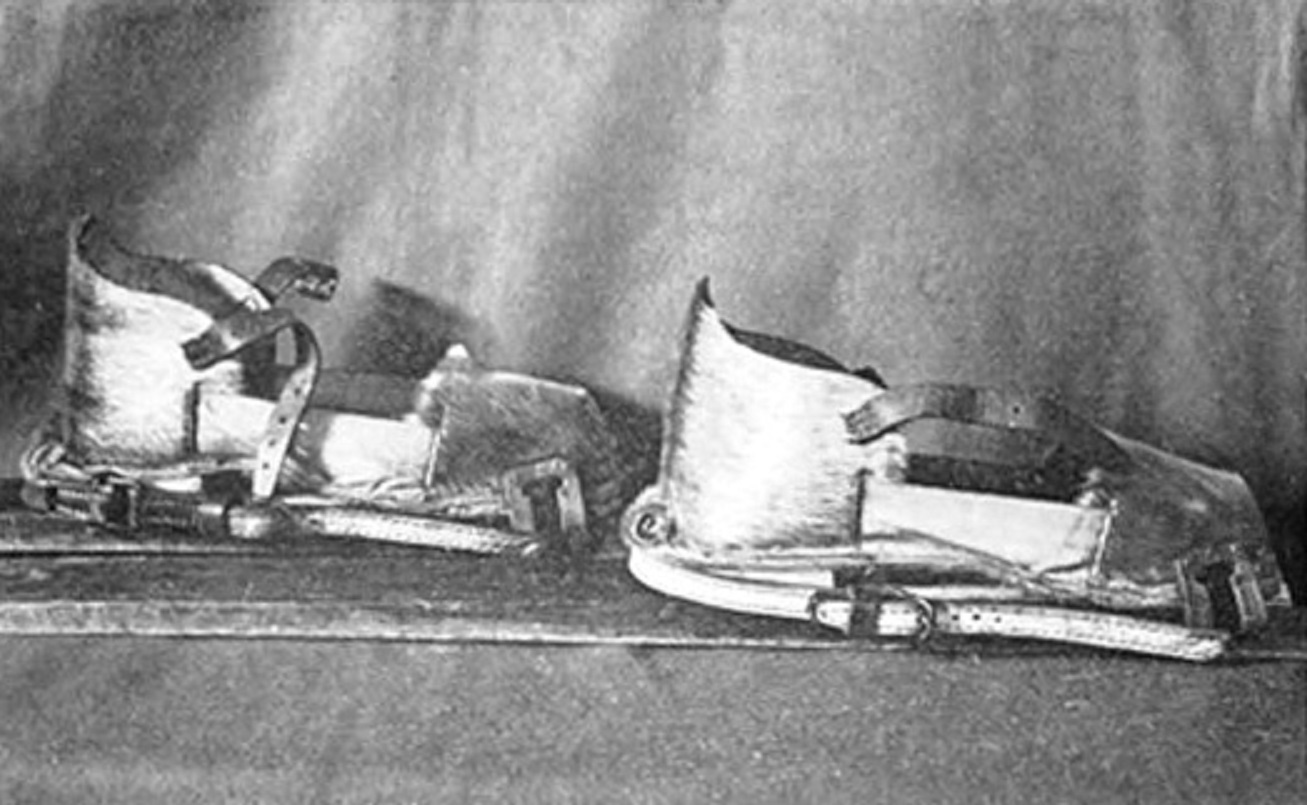

At first, Scott was hailed as a tragic hero. As the years went on, people began to question Scott’s methods and planning. He relied on ponies and motorized sledges, both of which proved extremely ineffective, while Amundsen used skis and dogs.

Royal Museums Greenwich, Picryl

Royal Museums Greenwich, Picryl

His Rival Wasn't Messing Around

There’s also the fact that Amundsen made no claims to a “scientific” expedition. He simply wanted to get to the South Pole. He didn’t collect any fossils to lug back with him.

Daniel Georg Nyblin, Wikimedia Commons

Daniel Georg Nyblin, Wikimedia Commons

He Made A Small Difference At Least

We should point out that the plant fossils found with Scott’s crew were the first to prove that Antarctica had once been covered in forests, an integral step in proving the theory of Continental Drift.

Scanned from the book Les Grands Explorateurs. Picryl

Scanned from the book Les Grands Explorateurs. Picryl

Chance And Circumstance

Despite the Terra Nova expedition's shortcomings, modern historians aren’t quite so quick to judge Scott. Sure, he didn’t do everything perfectly, but in the end, Antarctica is a truly brutal place.

Mother Nature Doesn't Care

Antarctica doesn’t care about how well anyone like Robert Scott or Roald Amundsen has planned. Sometimes, temperatures will simply plummet to -40 and stay there for days. It happened to Scott, and it didn’t happen to Amundsen. Sadly, it’s probably as simple as that.