The dreaded disease scurvy terrorized the seafaring nations for centuries. It cut down more sailors than enemy cannon fire, crippled expeditions, and rocked naval fleets. The cause was simple: a severe deficiency of vitamin C. Scurvy progressed through bleeding gums, joint pain, fatigue, and an untimely demise. When the cure finally emerged, it revolutionized sea travel, but it still took decades of unnecessary suffering and snail-like scientific progress.

Life At Sea Before The Cure

In the Age of Exploration, voyages could take months or even years. Fresh fruits and vegetables spoiled quickly, leaving crews to live on salted meat, hardtack, and dried legumes, none of which was a source of vitamin C. Sailors commonly contracted the gruesome symptoms of scurvy after 8–12 weeks at sea. The mortality rate on long voyages was sobering; for example, Vasco da Gama lost over half his crew to the dread disease during an expedition to India.

Alberto Cutileiro, Wikimedia Commons

Alberto Cutileiro, Wikimedia Commons

The Man Who Cured Scurvy

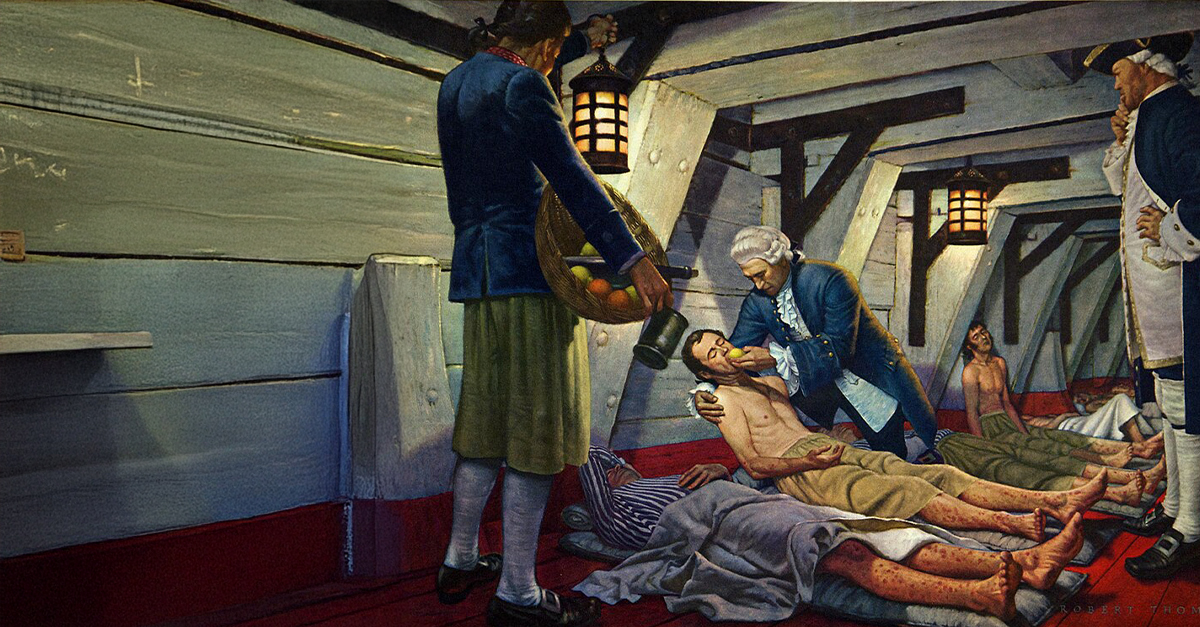

The man most credited with finding the cure for scurvy is Scottish naval surgeon James Lind. In 1747, while serving aboard HMS Salisbury, Lind carried out what we would now call clinical trials, the first of their kind. He chose 12 sailors who had scurvy and split them into six groups. He then proceeded to give each of them a different dietary supplement. The pair who ate oranges and lemons made a great recovery in a matter of days, while the others still languished.

Lind’s Finding Didn’t Raise Eyebrows

Lind published his findings in A Treatise of the Scurvy (1753), but his recommendations didn’t catch on at first. The Royal Navy was still skeptical, partly because of logistical issues and wrog ideas about the nature of disease. Lind himself downplayed citrus juice in his conclusions, muddling the clarity of his results. It wasn’t until decades later in the 1790s that the cure was finally adopted on a widespread basis.

George Chalmers, Wikimedia Commons

George Chalmers, Wikimedia Commons

Sir Gilbert Blane Made It Policy

The general implementation of citrus juice as a naval standard was the result of the efforts of Sir Gilbert Blane, a doctor who served on the Board of the Admiralty. Blane was a strong advocate of Lind’s work and pushed for daily lemon juice rations for sailors. In 1795, the British Navy officially commenced issuing lemon juice on long voyages. The measure had immediate and profound results: scurvy virtually from the fleet.

Impact On Sea Travel And Global Power

The eradication of scurvy had a major impact on maritime power. Sailors could maintain their health on long voyages, reducing casualties and the occurrence of mutinies. British sea power grew, allowing Britain to maintain the key trade routes necessary to support its global empire. With fewer medical crises onboard, ships could go further, map unknown territories, and return with intact crews. Empire and colonization were suddenly a lot more manageable.

Robert Alan - Parke, Davis & Company, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Alan - Parke, Davis & Company, Wikimedia Commons

Legacy And A Nickname

Lemon juice was eventually substituted with cheaper lime juice from British colonies. This is where sailors got the nickname “limeys.” While limes don’t have as much vitamin C as lemons, they were still good enough to prevent scurvy in most cases. The nickname stuck and is still a cultural reference to British sailors today.

Why The Lesson Still Matters Today

The story of scurvy shows how slow institutions can sometimes be to adopt life-saving science. Lind's basic experiment saved thousands of lives, but it still took decades for the meaning of the results to come into full use. We can certainly apply this lesson to today’s push for more medical progress.

You May Also Like:

Nasty Meals Americans Loved In The 18th Century

The 40 Worst Sea Disasters In History